Father Horacio Medina is a Roman Catholic priest serving in the Archdiocese of Newark, New Jersey, with a background that bridges theology, philosophy, and the humanities. Educated in Central America and Europe, Father Horacio Medina studied philosophy and humanities in Costa Rica, theology and sacred Scripture in El Salvador, and moral theology in Rome at the Scuola Alfonsiana. He also holds a bachelor’s degree in communication and journalism from Honduras. Alongside his pastoral ministry, he teaches subjects including ancient Greek philosophy, ethics, and Spanish as a second language at Saint Peter’s University in Jersey City. His academic interests include dramatic and romantic literature, with a particular focus on Shakespeare. Through this lens, Father Horacio Medina examines how literary depictions of heroism reflect moral struggle, sacrifice, and human limitation, themes that align closely with theological reflection and ethical inquiry. His engagement with literature complements his broader commitment to education, spiritual formation, and service to diverse communities.

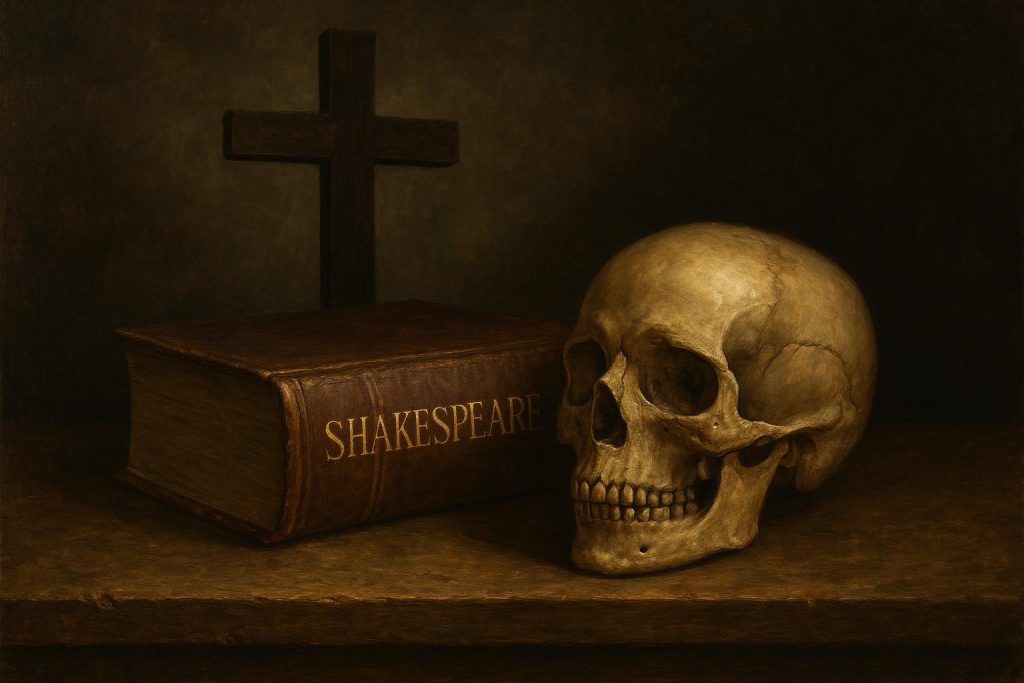

Understanding Tragic Heroism in Shakespeare

One characteristic of many of Shakespeare’s most memorable characters is their demonstration of heroism in trying circumstances. This definition of the hero is not defined by results in battle or wearing a crown, but in persevering through tragic and tangled events that can set even the most brave and well-intentioned person reeling.

An example is the celebrated warrior Lord Talbot in “Henry VI,” who sends for his son, whom he hopes to train and mentor, after great victories in Roan and Orleance. Unfortunately, the young John Talbot arrives just as the battle of Bordeaux is raging. The older John urges his son to flee from the much larger French force, in order to avoid certain death. The son heroically refuses to leave his father’s side and they both ultimately perish.

As he sustains a mortal wound, Lord Talbot thinks only of his brave son, exhorting “Where is my other life? Mine own is gone./ O, where’s young Talbot?…Triumphant Death, smeared with captivity/Young Talbot’s valor makes me smile at thee.”

He goes on to compare his tragically defeated son to the hero of Ancient Greek legend, who flew his chariot too close to the sun: “And in that sea of blood, my boy did drench/His over-mounting spirit; and there he died/ My Icarus, my blossom, in his pride.”

If this depiction of heroism brings focus to sacrifice as being an essential component, in King Lear, Shakespeare envisions the ultimate tragic hero: what he has accomplished in battle is of far less importance than what he accomplishes in old age, as a blind man with faculties much diminished.

Deciding to split his kingdom between three daughters, King Lear foolishly places his greatest trust in the two daughters Goneril and Regan, who go on to practice deceit, employing their power against him. As Lear loses everything he once had, he enters the wilderness as an insane man bereft of ruling authority and possessions, and without even the authority he once had as a father.

In this maelstrom, only his youngest daughter Cordelia remains true. King Lear comes to understand that her enduring love alone can help him take steps toward admitting mistakes and finding redemption. He heroically swallows the pill of self pride, admitting that he was wrong in his actions, mentally enfeebled, and not in his right mind. This provides a tentative step toward a redemption narrative.

Unfortunately, Lear and Cordelia are captured by the Machiavellian and vengeful Edmund, who spares Lear while putting his Cordelia to death. This is Shakespeare at his most pessimistic: he seems to be saying that a heroic evolution in character is not enough to overcome a grim society in which traitorous, divisive actions are exalted.

In the Tragedy of Troilus and Cressida, Shakespeare turns his attention to the Trojan War, which in the hands of Homer in the Iliad yielded heroes galore, including Achilles and Hector. However, by the Bard’s reckoning these great warriors are petty and, imbued with overweening pride, to be pitied rather than celebrated. Rather than exalting the glory of conflict, he focuses on the quiet, tragic heroism embodied by Troilus and Cressida, a pair of star-crossed lovers torn asunder by conflict. They sacrifice all by maintaining an unbreakable love, despite being on opposing sides.

About Father Horacio Medina

Father Horacio Medina is a Roman Catholic priest in the Archdiocese of Newark who combines pastoral ministry with academic teaching and community service. He has studied philosophy, theology, sacred Scripture, and moral theology in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Rome, and Honduras. Father Medina teaches ethics, ancient philosophy, and language studies at Saint Peter’s University and regularly serves hospitals and prisons in New Jersey. His interests include Shakespeare and dramatic literature, which he approaches as sources of moral reflection and insight into human character.